Coming from a non-Computer Science related field but find yourself having a hard time navigating data analysis? I won’t blame you if you feel at a loss as to where you should begin?

Posts like which language should you learn for datascience often catch our eyes and it’s no different whether you’re doing bioinformatics or something far removed such as HR analytics.

The only advise I have is to immerse yourself as much as you can whenever you get the chance. This way you’ll be able to gain EXP little by little.

There’s even a level up tree starting from a junior Bioinformatics analyst to a full on role, much like how it was described in this post.

Below’s a list of skills I’ve successfully mastered in 2016.

Now lets count down from number 10!

10. Mixing procedural scripts with Object Oriented Programming (OOP)

Previously, I’ve organised my research analyses as scripts with running numbers. Mainly procedural stuff…

ProjName.0100.doTask1.R

ProjName.0101.doTask2.py

.

.

ProjName.0109.doTask3.pl

But quickly realised much of the analyses I do is often not at all linear.

It often works as like a networks. ScriptN+10 needs ScriptN+2 functions, there’s dependency when the project works up to a relatively medium->small size.

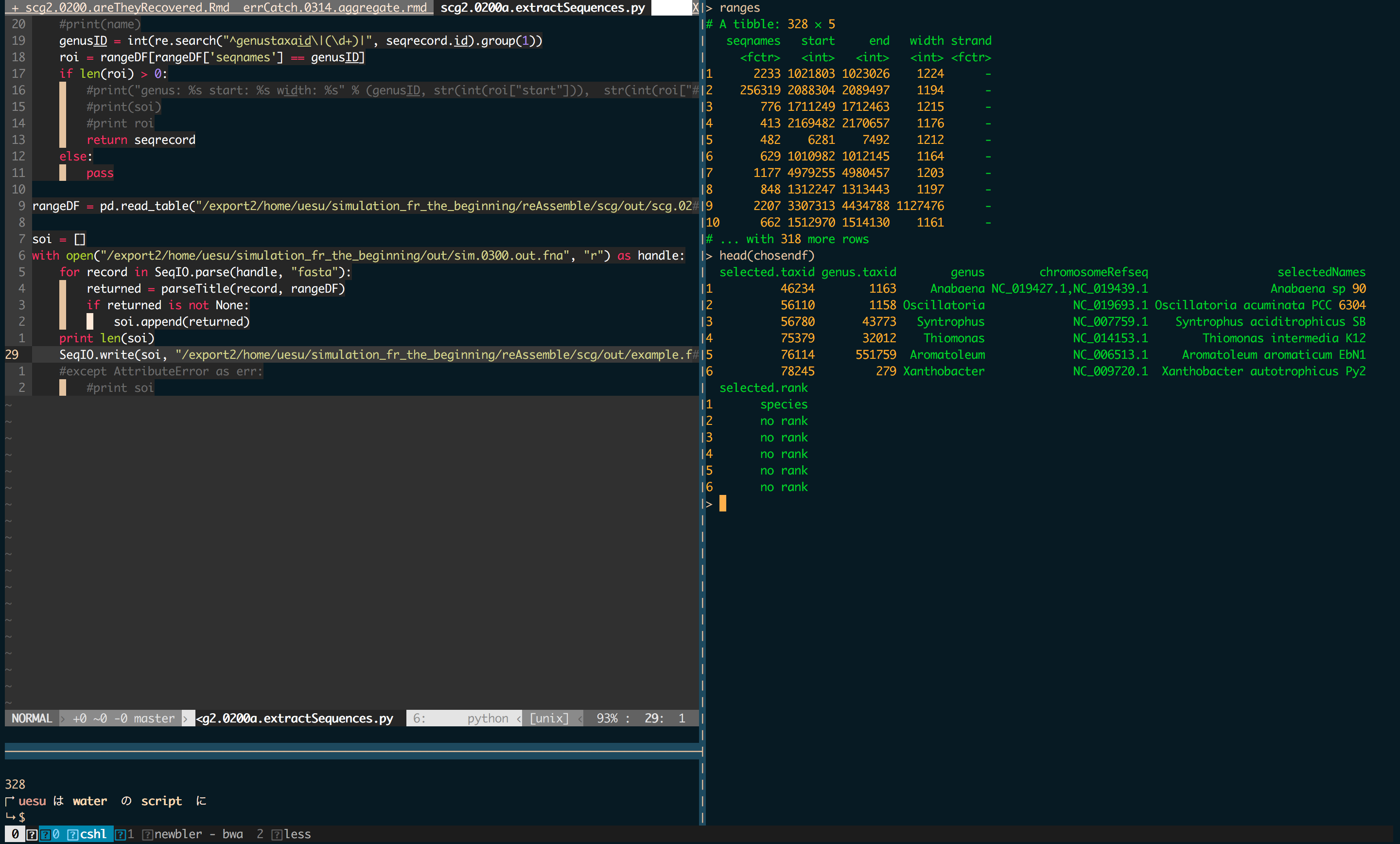

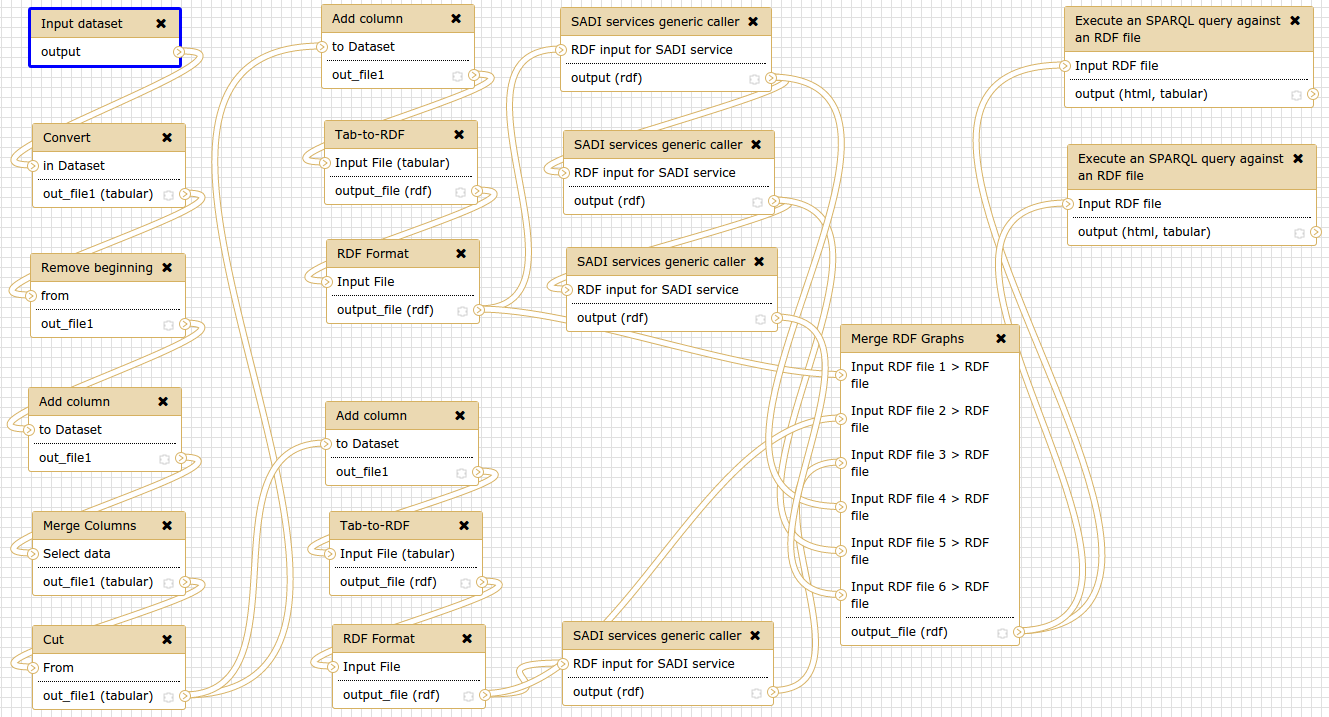

The above is a screenshot of the dependency network using galaxy workflow. It nicely summarises some of what I do. I searched around for a CLI version and stumbled upon Luigi

In 2016, I tried using luigi (python package from spotify to deal scheduled tasks) but found it too complicated for something I could solve simply by doing OOP. Not everything is a routine operation but dependencies on another hand is a real thing.

What OOP does is it allows you to use design patterns. Design patterns are predefined solutions to specific kinds of problems, proven over time and known by the software community, but just remember not to get too obsessed with it. By using OOP, functions and methods are quickly abstracted away and gives you cleaner analysis code (class and methods)[https://www.sitepoint.com/object-oriented-javascript-deep-dive-es6-classes/].

One of the things which I see myself doing more going into 2017 is to apply more OOP design patterns.

9. Package your code

To be honest R users are rather spoilt by R’s fantastic package system, CRAN. It’s extremely easy to download and install, and share your pacakges.

Hadley’s devtools package is close to sorcery. (Do check out more of his packages, collectively known as hadleyverse)

When I looked outside of R, at other ecosystems like Python’s PyPI and Perl’s CPAN, things just dont feel as easy.

If you’re hacking in Perl, check out minila As for Python, one rather interesting find is the templating package cookie cutter package which makes templates python modules.

Both allows you to upload your package to github and let other install from it directly.

You might be kind of confused why am I still mentioning Perl, well that’s because much of Bioinformatics is still using it!

8. Be a polyglot for package management systems

Because bioinformatics software are written in almost any language imaginable, eg. Erlang, Haskell, Perl, C++, Java, Python2.X, Python3.X, you name it its there. Learning how to use them is always be the constant, however familiarise yourself with common installation methods like make will make a whole of a difference.

This parallels Web development quite a fair bit. In my startup life at fundMyLife we adopted meteorJS, a modern ES6 web development framework and at fundMyLife we use coffeescript coupled with jade/pug. Javascript’s package system NPM is a beast but once you get a hang of it many of its sweet packages will be at your fingertimes.

The community is quick to adopt and change, everyone wants you to use their standards and formats. One thing is clear, what stays constant are their package managers, so know them well.

7. Document your projects

Read enough documentation either for installation or just simply to use the functions in a project, you’ll soon see yourself transforming into a connoisseur of sorts as to what makes documentation good. Its extremely important if you want people using your work and its just plain courtesy.

R’s Roxygen is extremely useful. It is by far the most user friendly way to document your R code.

Below is how you would go about annotating a function in your package and the docs are all automatically generated

#' Add together two numbers.

#'

#' @param x A number.

#' @param y A number. #' @return The sum of \code{x} and \code{y}.

#' @examples #' add(1, 1)

#' add(10, 1) add <- function(x, y) { x + y }

I’m still learning Python’s documentation system.

PERL has its POD documentation system which allows you to embed documentation between code. But it’s very clunky. I used this in my pAss package but still it can’t beat R

6. Containers, Containers, Containers.

Most of us nowadays start off their journey in serverside analysis in a debian linux distro, usually an Ubuntu box, with full root access while enjoying the privileges to run package manager 📦 apt-get

as and when you please without even blinking and eye.

But when we start using a shared resource things quickly turn south. The inspiration to start incorporating this into my workflow came when i saw the web community picking this up to deal with dependency hell. Meanwhile I found out one of my mentors, who is now working in heavily in industry data science uses docker in his day to day life.

What containers really do is disrupt is MAKE. So instead often confusing makefiles, one writes dockerfiles and everything that gets installed stays within the container without polluting your host environment, pretty much like a function.

Docker is the most mainstream of all container technologies and you should take a look at the biocontainers github page, there you can find many bioinformatics softwares containerized!

Don’t worry about accessing your files from your home directory, it isn’t a problem as Docker lets you mount the host system’s HDD onto the running container.

Docker is like building a HDD in minecraft

Talk about inception

Together this solves an acute problem as it gives the normal user back the ability to be root without ruining the rest of the host system and still have performance similar to running on bare metal.

One disadvantage of using Docker is installing docker itself requires root access and if you’re dealing with a university wide shared resource good luck.

Which is why #5 linuxbrew is go out to be helpful

5. Linuxbrew

Linuxbrew is basically a port of the macOS/OSX package manager HomeBrew . So if you’re already familiar with homebrew, linuxbrew will be a breeze.

Just how easy is it?

Lets try installing R, wait lets make it a tad bit more difficult, lets try to customize the installation further with the newest fastest basic algebra algos included in openblas

brew install R --with-openblas

Tada, you’re done. Yes, its that simple.

What Homebrew or in this case Linuxbrew lets you do is not only lets to install into your $HOME directory, bypassing all that superuser bullshit, it also lets you do very specific installations and dependencies.

Steve jackman (see his slides) and many others are behind the Science tap of with instructions for linuxbrew/homebrew to install popular bioinformatics tools.

This makes installing and ultimately doing science much easier than before.

If you’re still confused about how to do local installations, i recommend reading this post, although its title has Python, its really meant for everything.

4. Rmarkdown

To be honest I started r markdown way back in 2015 but got really into it in 2016 because it really helps frame my questions and analyses.

Writting your analyses as Rmarkdowns force you to place those tiny bursts effort and energy into a single compiled document with clearly defined goals and development of the story.

Rmarkdown has a interpreter engine so it allows you to not only work with R but with Perl or python.

Having docker installed also allowed me to use the newer versions of Rmarkdown, rmarkdown2.

One feature I absolutely love is auto code hiding in the output html.

The output looks absolutely professional and when you need it you could always show the code.

Interestingly, the Rstudio team has also come up with R notebooks. I’m sure many pythonistas will love this new feature but personally for me I’m very happy with the way things are for rmarkdown all I’m giving this a miss.

3. Tmux-vim-slime

For those who know me in person, you know I’m a big fan of the terminal. And I do most of my work if not all in that one window. So when I’m in the server I’ll always have a tmux session running

This is a good tutorial and it teaches how to work with R in the server like a cluster away from familiar Rstudios. Recently I’ve switched from this to vim-slime a vim port of the Emacs slime cause it also supports IPYTHON.

2. BioJS

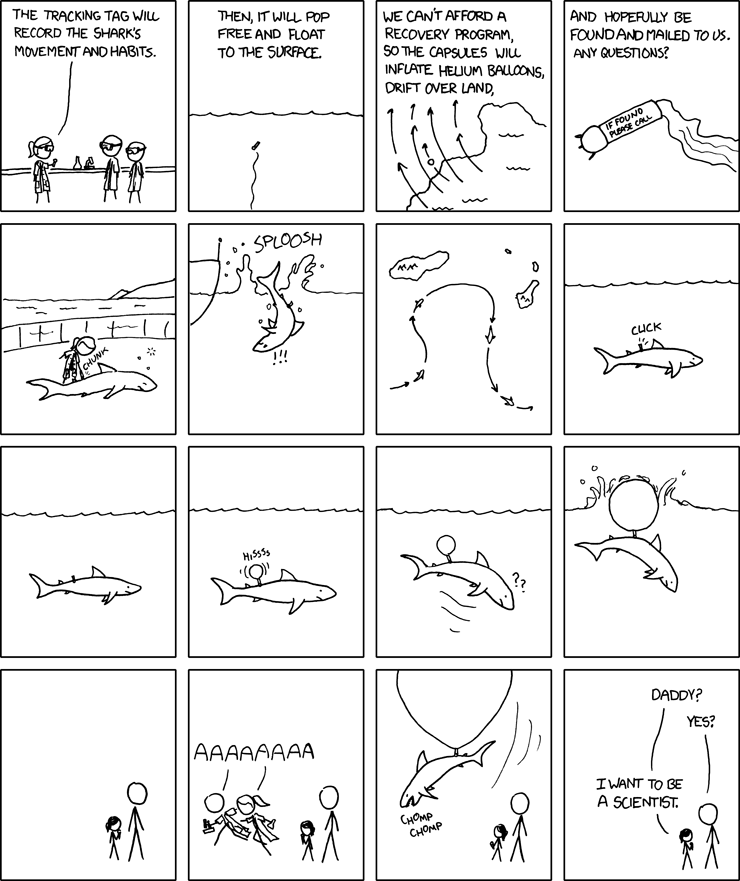

Learning web development, while building fundMyLife has given me the skills required to build the UI layer instead of CLI system tools using python/perl/R.

BioJS is one of those interesting developments where important visualisations are now rendered in a browser and hence any operating system. You see this trend outside of bioinformatics where editors like Atom and Visual Studio Code, and communications tool Slack are all built as a browser based application.

The admins are were even featured in 2016’s GSoC checkout the blogpost part2, part2 where they went on to build visualisation for the Game Of Thrones

1. Writing production ready code

There’s a lot of talk about reproducibility and really much of it has been solved in the industry. Nearing the end of the PhD, means most of my packages should be ready for use by the public at large.

Personally, I’m aspiring to be able to write code good enough for a industry setting. The crossover from academia into industry isn’t that uncommon, here’s a post about a nucelar physicist who is now working in UBER and doing both datascience and shipping production code some even do some engineering as well

Thats all folk’s! I hope this helped you get orientated around Bioinformatics.

If you know any good workflows please do share with me.

comments powered by Disqus